Health & Fitness • 05 Jun 2018

Is the Price of Beauty sometimes too High?

According to the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders, nearly 70 percent of girls in grades 5 through 12 said magazine images influence their ideals of a perfect body. The National Institute of Health estimates the lifetime prevalence of anorexia and bulimia is 0.6 percent of the U.S. adult population, but among 13- to 18-year-olds, it is 2.7 percent. There are numerous risk factors, including being female, age (eating disorders are most common in the teens and early 20s), family history and influence, as well as the presence of additional mental health issues.

Exposure to thin models could play a role. Yet little hard data exists about whether or not the ubiquity of ultra-thin models causes people outside the industry to develop disordered eating or full-blown eating disorders. Although thin models may not be the direct cause of eating disorders, they can be a trigger or a factor in maintaining an eating disorder. In other words, if a woman has a predisposition for an eating disorder and spends a lot of time looking at fashion magazines, this can be one of the factors that triggers feeling bad about her body, which she then turns into eating disorder behaviour, like excessive dieting. Much research has suggested a relationship between the two, though Dr. Anne E. Becker, a professor of Global Health and Social Medicine at Harvard Medical School, said there has not been any single, definitive scientific study.

Despite protestations by women who recognise the danger of portraying any one body type as “perfect”, the situation is not improving. If we look back at the heady days of the supermodels in the late 80s and early 90s, beauties such as Cindy Crawford, Eva Herzigová and Claudia Schiffer look positively curvaceous compared to the models of today.

“It is the ultimate vicious cycle”

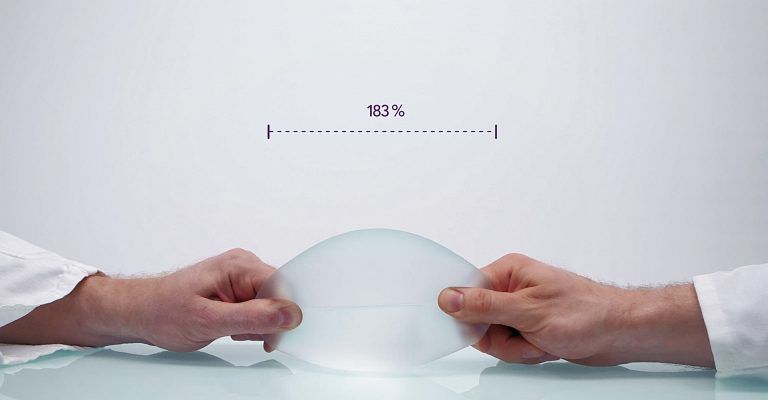

It is the ultimate vicious cycle. A model who puts on a few kilos can’t get into a sample size on a casting and gets reprimanded by her agency. She begins to diet, loses the weight, and is praised by all for how good she looks. But instead of staying at that weight, and trying to maintain it through a sensible diet and exercise, she thinks losing more will make her even more desirable. And no one tells her to stop. Likewise, girls who can’t diet their breasts away will have surgical reductions. While this approach may deal with the physical aspect of the problem, it may accentuate the underlying psychological issues. Instead of feeling satisfied with the achieved result, many girls then enter into dangerous patterns of behaviour. This is generally accompanied by mood swings, extreme fatigue, binge eating and sometimes bouts of self-harming. All in the quest to feel and be seen as beautiful.

It remains the responsibility of health care professionals, such as nutritionists, psychologists and plastic surgeons to provide adequate advice and warn about such catastrophic consequences, before initiating any treatment. However, and without trying to push over the responsibility form our part as doctors, the real shift towards a healthy mindset will not occur without first a change in the culture that is constantly projected in our public media.